We gathered with our cousins that Thursday to clear out Grandma’s small house on Linden Road. Mother had prepared her most politically-correct suggestion: each grandchild could choose just one item of Grandma’s to take with them, but any remaining item of their choice. Mother always worked through things in an order that began at practical and eventually ended at emotional. She kept her emotions private in this way, facing it all herself only once all of the public and social expectations were long past. The aunts and uncles had already taken what they wanted from Grandma’s, though looking around that day, I didn’t notice anything missing. I must not have paid enough attention; what does that say about me? Sad, how a person makes so many choices to arrange their world around them, with no guarantees that anyone will even notice, let alone remember once they’re gone. I look around again and focus instead on all that I do remember: the dark mahogany upright piano, the orange upholstered wingback chair, the lovely grandfather clock in its regal, carved wood casing. The rest of her things would be sold off in the estate sale this weekend, to help pay the bills that were left from the funeral.

The picking would begin with Louis, the youngest, as Mother’s reasoning suggested he had spent the least time with Grandma, and might have less connections, therefore, to her things. We would work our way up through our ages after him. Louis chose a wooden vintage radio with black dials worn shiny from regular use. The radio used to sit on the tiny green formica-topped kitchen table, so Grandma could listen to the oldies’ station as she washed the dishes each night. We let Patty pick long-distance at number two, on a phone call from Portland. She chose the three-tiered rope macrame plant stand that hung in the corner of the living room from the ornate gold ceiling hook. A very fashionable choice - Patty was always informed on the trends. On and on our choices went, through all seven grandchildren: a marbled ceramic lamp; a full poker set in a round, red leather case with gold snaps; a bonsai tree planted in a rough cement planter; and an etched mirror that had always hung in the front hall. Their choices matched their personalities perfectly, ranging from understated to ornamental, from small to large, from sentimental to valuable. In my role as oldest grandchild, I chose last. I knew just what I wanted, though I knew no one else would choose it. I had to look around a few places to find it, but finally my eyes caught its form, tucked into the corner of the spare room closet: Grandma’s old, battered yardstick.

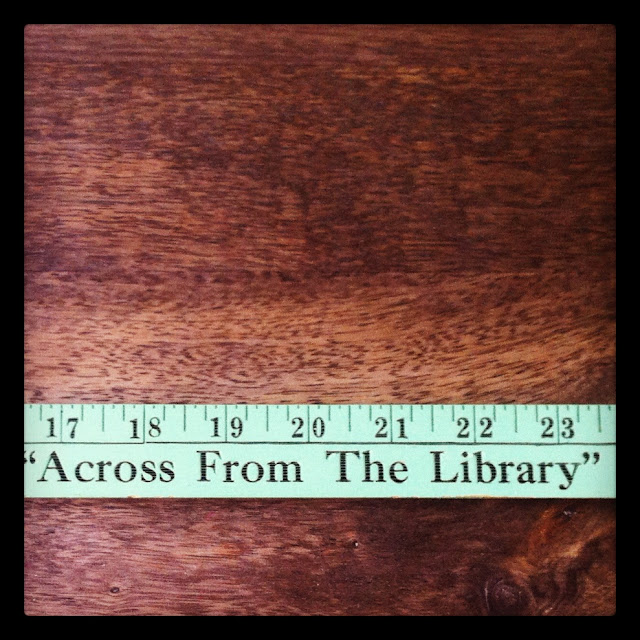

The wooden yardstick’s edges were worn and slightly splintered from all its years of use. It was painted a dusty shade of bluish-green, printed with black letters that had worn through to show the pattern of its wood grain below, the same message pressed firmly into both sides. Grandma had the yardstick for as long as I can remember - I have no idea when, or where exactly, she got it. Yardsticks are the sorts of things that seem to come from nowhere, but are always with you, like a subsidiary family member, floating from room to room throughout the years, always belonging, but never stealing attention. It was always handy for a school poster project or for Grandma’s sewing stints. Her yardstick obviously must have come from The Carpet Center - perhaps she bought her carpet there long ago? Or maybe it was a promotional item, given away at the local hardware store as a way to draw more customers in? No one seems to have any idea of its origins, nor does it seem anyone cares to care, except for me. But we can all attest to the faithfulness of its company through all our growing-up years. I loved all the marks the yardstick had collected along the way: bits of pencil and Sharpie marker and an occasional ballpoint scribble on its painted surface, where a little brother or sister had “helped” with a project. “Delusions of grandeur,” my father always said, about our humble town and its street names that conjured up images of other places. “Park Avenue,” with its reference to fancy New York City, or “Vincennes,” which was most well-known for being a nearby Indiana town, but actually referred originally to a suburb on the outskirts of Paris. I had done a research project on Vincennes for school, and learned that the French town boasted both a zoo and a castle, where the Marquis de Sade was once imprisoned. I could only imagine. It was just like our town, to move your thoughts on off to something else, something far away and most definitely better. Even “Western, Kedzie, Ashland and Halstead” made you feel as if you were just a stone’s throw from the city limits where those streets belonged, when in reality, it was at least a thirty-mile drive. It always bothered me especially that one of the nearest main roads was called the “Dixie Highway.” Wasn’t that the worst of all? We had learned early in school about the Civil War, and what I learned then had already ruined one of my favorite songs on the Disney cassette: “Away, away, away down South in Dixie!” So upbeat, so triumphant, so misleading - it almost gave you understanding for those poor Confederates. Maybe the song was what had kept them going. I still loved it secretly, but felt the impropriety of claiming sympathy for the southern slave-states’ case. What was a “Dixie Highway” doing up here in Illinois, anyway?

Everyone knew where the Library was. It was as good a landmark as any. After all, carpets were not the sort of thing that people shopped for regularly, and while a name like “The Carpet Center” guaranteed a clear offering of products, it did not do much to distinguish itself from other carpet retailers in the area. Homewood’s place as a part of Cook County meant the shop was included in the giant phonebooks, as well as the local ones. The free books, most commonly used as booster seats for children or step stools for housewives, showed up once or twice a year on everyone’s front step, in shades of yellow and white, and almost always decorated with accents of blue. Turn the pages to “Carpets,” and there it would be, three pages in, a square box interrupting the rest of the column, containing the same famous quotation.

And I remember my own last mark, the year I turned twenty-one, which Grandma had determined as the age we would be fully-grown. In my last year of school, I was beginning to understand what growing up might really mean, and that I wanted my life to count in ways just as tangible as the marks on Grandma’s wall. Grandma added my age to the line that had held its place for several years now: five feet, five inches, four inches taller than she was. She touched my cheek, with her left hand and said nothing; she didn’t have to, her eyes beamed bright and proud at the woman I was becoming. Most of the kids looked at the wall as something they had done for Grandma, year after year, humoring her old-fashioned whims and routines. I looked at the wall as something Grandma had done for us.

(Read more about my "objects" writing prompt series here!)

This is beyond beautiful.

ReplyDeleteI, for one, am glad you picked the yardstick. (:

Thank you!!!!!! :) So kind! Made my day, truly!

ReplyDelete